Calculating (1/2)! by Lattice Point Counting

Abstract. Here we’ll define $z! = \Gamma(z+1)$ which is standard practice.

We’ll start with an analytical lemma relating a function’s power series coefficient asymptotics to the values of the function itself. We’ll apply that to a function which is related to lattice points inside a circle.

Lemma. Suppose $a_0, a_1, \ldots$ is a sequence of real numbers, and write $A(t) = \sum_{n \leq t} a_n$.

\[\liminf_{t \to \infty} \frac{A(t)}{t^r} \leq \liminf_{x \to 1^-} \frac{(1-x)^r}{r!} a(x) \leq \limsup_{x \to 1^-} \frac{(1-x)^r}{r!} a(x) \leq \limsup_{t \to \infty} \frac{A(t)}{t^r}\]

Assume that for some $r > -1$, we have $A(t) = O(t^r)$.

Then the function $a(x) = \sum a_n x^n$ converges absolutely for all $|x| < 1$, and

Proof. We’ll recall the definition of $r!$ here as we’ll need it in a second.

\[r! = \Gamma(1+r) = \int_0^\infty u^r e^{-u} du\]To prove the lemma, it suffices to show only the inequality involving the lim sups, since the other inequalities are an easy consequence of that one.

So let $\varepsilon > 0$ be arbitrary and write $\delta$ for the quantity $\limsup A(t)/t^r$.

Then there exists $t_0 \geq 0$ so that for all $t \geq t_0$, we have $A(t) \leq (\delta + \varepsilon) t^r$.

To relate $a(x)$ to $A(t)$, we use Abel’s summation theorem to obtain

\[a(x) = -\log(x) \int_0^\infty A(t)x^t dt\]which is valid for $0 < x < 1$. We can immediately relate this to $\delta, \varepsilon$:

\[\begin{align*} a(x) &= \left\lbrack-\log(x) \int_0^{t_0} A(t)x^tdt\right\rbrack + \left\lbrack- \log(x) \int_{t_0}^\infty A(t)x^tdt\right\rbrack\\ &\leq \left\lbrack-\log(x) \int_0^{t_0} A(t)dt\right\rbrack + \left\lbrack- \log(x) \int_{t_0}^\infty (\delta+\varepsilon)t^r x^tdt\right\rbrack \end{align*}\]We can bound the second term as

\[\begin{align*} - \log(x) \int_{t_0}^\infty (\delta+\varepsilon)t^r x^tdt &\leq - \log(x) \int_{0}^\infty (\delta+\varepsilon)t^r x^tdt\\ &= (\delta+\varepsilon) \cdot \left\lbrack -\log(x) \int_0^\infty t^r x^t dt \right\rbrack \end{align*}\]To continue we use the substitution $x^t = e^{-u}$, obtaining

\[\begin{align*} (\delta+\varepsilon) \cdot \left\lbrack -\log(x) \int_0^\infty (-u/\log(x))^r e^{-u} \cdot \frac{du}{-\log(x)} \right\rbrack &= (\delta+\varepsilon) \cdot \int_0^\infty (-u/\log(x))^r e^{-u} du\\ &= (\delta+\varepsilon) \cdot (-\log(x))^{-r} \int_0^\infty u^r e^{-u} du\\ &= (\delta+\varepsilon) \cdot (-\log(x))^{-r} r! \end{align*}\]Now using $-\log(x) \sim 1-x$ as $x$ tends to zero from below, we have the following:

\[\begin{align*} \frac{(1-x)^r}{r!} a(x) &\leq O((1-x)^{r+1}) + (\delta + \varepsilon)(1 + o(1)) \end{align*}\]Because $r > -1$ we have the desired inequalities as $x \to 1$ from below. $\newcommand{\proofqed}{\quad\quad\quad\square} \proofqed$

That’s the extent of the integral manipulation we need to use for this proof.

Considering $(1/2)!$ leads us immediately to sequences $a_n$ such that $a_0 + \ldots + a_n \sim \sqrt{n}$.

The obvious choice is to set $a_n = 1$ if $n$ is a square and $0$ otherwise.

We then have

\[a(x) = \sum a_n x^n = \sum_{n \geq 0} x^{n^2}\]and by the analytical lemma we have

\[\lim_{x \to 1} \frac{(1-x)^{1/2}}{(1/2)!} a(x) = 1\]We can square this and simplify to obtain

\[\lim_{x \to 1} (1-x) a(x)^2 = \left\lbrack (1/2)! \right\rbrack^2\]The plan will be to look at the coefficients of $a(x)^2$ and use the lemma again.

Write $a(x)^2 = \sum c_n x^n$. Each $c_n$ will equal $\sum a_i a_{n-i}$, which ends up being the number of ways to write $n$ as a sum of two non-negative squares. We can then interpret $c_0 + c_1 + \ldots + c_n$ as the number of lattice points in the non-negative quarter circle of radius $\sqrt{n}$.

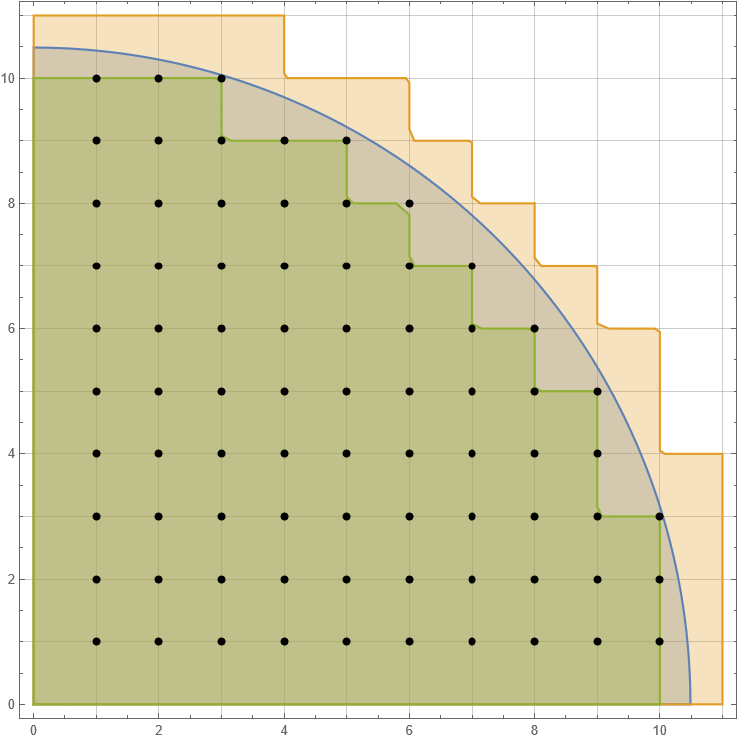

Write $N(r)$ for the number of lattice points in the non-negative quarter circle of radius $r$, and $S(r) = \frac{\pi}{4} r^2$ for its area. We’ll quickly show that $N(r) \sim S(r)$.

Associate each lattice point $(x, y)$ with the unit square $\lbrack x, x+1\rbrack \times \lbrack y, y+1\rbrack$. These lattice points cover the quarter circle, and since each unit square has area one, we have $N(r) \geq S(r)$.

As for the other direction, associate every lattice point $(x, y)$ with nonzero coordinates with the unit square $\lbrack x-1, x \rbrack \times \lbrack y-1, y \rbrack$. All of these squares will together fit inside the quarter circle. The number of lattice points with no corresponding square is $2\lfloor r \rfloor + 1$, so that $N(r) - 2r - 1 \leq S(r)$.

Since $S(r)$ grows quadratically we have $N(r) \sim S(r)$ as desired.

So then, thinking back to the coefficients of $a(x)^2$,

\[c_0 + c_1 + \ldots + c_n \sim \frac{\pi}{4} (\sqrt{n})^2 = \frac{\pi}{4}n\]and by the lemma,

\[\lim_{x \to 1} (1-x)a(x)^2 = \frac{\pi}{4} = \left\lbrack(1/2)!\right\rbrack^2\]Take the square root to get $(1/2)! = \frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2}$. $\proofqed$

Addendum: $d$-Dimensional Balls

It’s actually very easy to use this machinery to find an expression for the volume of a $d$-dimensional ball.

Write $a(x)^d = f_0 + f_1 x + f_2 x^2 + \ldots$ where the coefficients $f$ will depend on $d$.

Then $f_0 + \ldots + f_n$ is the number of lattice points in the non-negative section of the $d$-ball of radius $\sqrt{n}$. Write $G(r)$ for the number of lattice points in the positive section of the $d$-ball with radius $r$, and write $H(r)$ for its volume. We’ll take for granted that $H(r) = H(1) r^d$, but you again have to prove that $H(r) \sim G(r)$. Basically the same trick as before works to show $G(r) = H(r) + O(r^{d-1})$.

So now, recalling the results from before:

\[\begin{align*} \lim_{x \to 1} (1-x)^{1/2} a(x) &= (1/2)!\\ \lim_{x \to 1} \frac{(1-x)^{d/2}}{(d/2)!} a(x)^d &= \frac{\lbrack (1/2)! \rbrack^d}{(d/2)!} \end{align*}\]but also by the lemma and counting, that limit is equal to $H(1)$, the volume of the positive section of the unit $d$-dimensional hypersphere. If we want the whole hypersphere instead, we multiply by $2^d$ to get

\[\frac{\lbrack (1/2)! \rbrack^d 2^d}{(d/2)!}\]